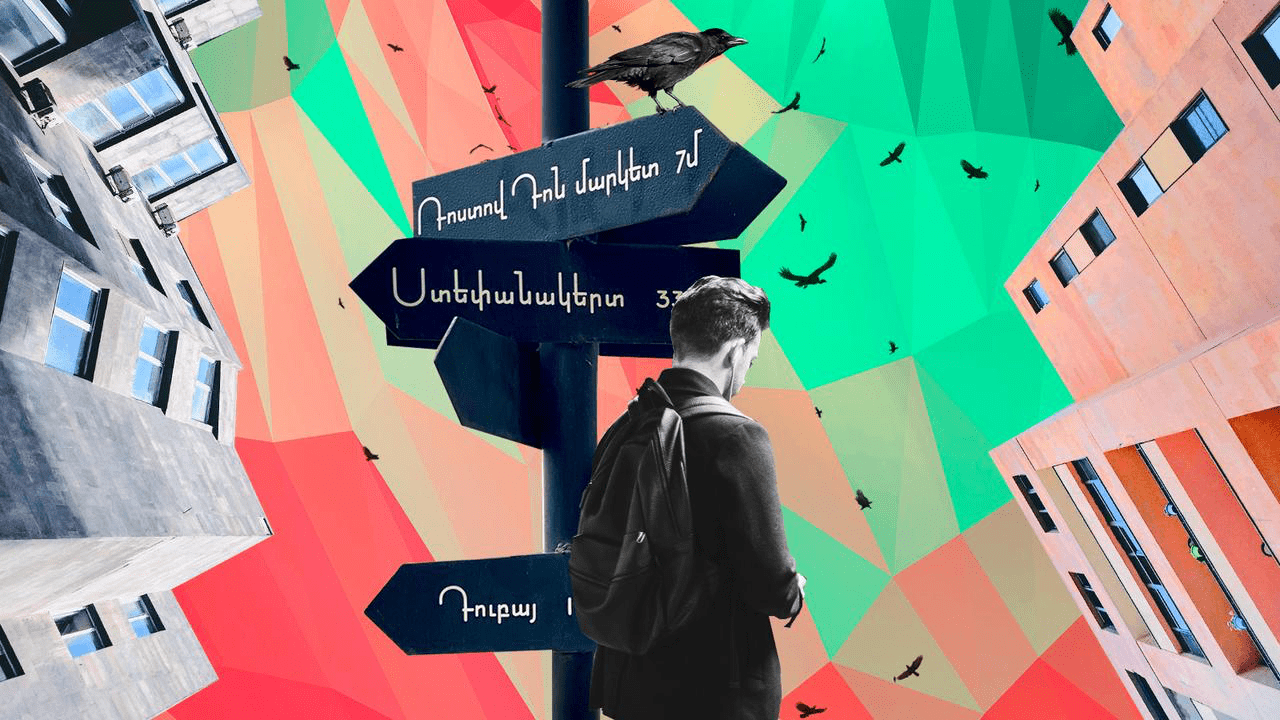

The topic of Russian political emigration in the context of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, which is the object of research in our article, is currently one of the most important, at the same time, difficult ones, the coverage of which is necessary to understand the trajectory of the Russian political opposition in the past and present, modern standing of its representatives: from opposition leaders to local political activists — standing both in Russian politics and outside of Russia. Emigration as such1, among other things, can be interpreted as a political gesture in itself: the citizens of a particular country “vote with their feet” with great aspiration, when the legal electoral mechanisms of influence on political processes are completely devalued, and the elections themselves are reduced to props. And in this sense, Russia has long been a sad example of just such a country from which we, its citizens, equally politicized and apolitical, actively “vote with our feet.” The article proposes to look at emigration as a political problem, at the same time highlight the possibility of politics in emigration. Especially against the backdrop of the extreme context in which emigrants from Russia found themselves after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It would not be an exaggeration to say that February 24, 2022, became a real existential challenge for emigration, prompting Russians to start looking for those grounds that would allow them to construct their subjectivity in a new way — based on the citizenship, representatives of the aggressor country, but also, being in a different level of integration into societies and countries of their new life (especially, of course, if we are talking about Western countries), show themselves as people who are in solidarity with Ukraine and Ukrainians in their struggle for the freedom and independence of their country.

There is a well-known opinion, actively shared by those who, despite the repressions and the obvious lack of prospects for legal political participation in modern Russia, remain inside the country, taking risks whose meaning is not so visible in the present (which does not rule out the moral capital they are now acquiring, the weight which may be of decisive importance in the future). This position can be summarized by the theses: “the state of affairs in the country cannot be influenced from abroad” and “those who left cannot speak on behalf of those who remain.” Emigration, concerning the fate of a politician, is sometimes perceived as the end of the career of a politician “in exile”, who now acts as an indifferent observer of the political processes unfolding in his homeland in his absence, which he no longer has the power to influence. However, it will suffice to refer to the biographies of just a few politicians and statesmen in the countries adjacent to Russia to understand how untenable this point of view can be. So the current president of Latvia, Egils Levits, is from a family that emigrated to Germany. Ex-president of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, whose argument with an associate of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny Leonid Volkov on the appropriateness of discussing an analog of the “Marshall Plan” for the future Russia caused such a heated discussion on social media2, was born outside the country, in the Swedish capital Stockholm, where his emigrant parents left to escape the advancing Soviet troops. A Georgian political and statesman Mikhail Saakashvili, the future leader of one of the first revolutions of a new type in the post-Soviet space, the “Rose Revolution” (Georgian ვარდების რევოლუცია), now a political prisoner in his homeland, spent several years in the United States and the European Union for educational and other purposes.

A textbook example from the recent historical past of more distant countries is the return to politics of people who found themselves forced to emigrate from the Franco regime in Spain, after almost forty years of Spanish dictatorship3. As can be seen from the above examples, emigration in the life of a politician is rather one of the stages of a rich and long biography, rather than a rigid border or line dividing life like a demarcation line at the “before” and “after” stages. As for Russian political activists, it must be admitted that for them emigration often becomes the only way out, allowing them to save themselves for the future and the future for themselves, without renouncing their beliefs and views and continuing political activism, albeit outside Russia. Once abroad, political activists from Russia secretly take on an equally important mission, albeit not so obvious to many, the mission of demonstrating to the society and country that accepted them that the Russian view of the world is wider than Putin’s (and with a high probability, directly opposes it), to become ambassadors of, if not “beautiful,” then another, non-Putin’s Russia, developing an important dialogue between foreigners and pro-democracy Russians.

The purpose of this work, which continues the series of articles on the non-authoritarian foundations of Russian society, is to highlight the phenomenon of “political emigration” and problematize the institutional building of the structures of the emigrant community. The latter is directly related to the topic of the politicization of emigration. One of the main questions, the answer to which is permanently revealed in the course of the article, can be formulated as follows: at what point do emigrants, whose departure from the country was not initially motivated by political reasons, acquire the character of political emigration? Another topic that is the focus of our attention is the prospects for the institutionalization of the Russian emigrant community, and the possibility of creating political institutions for emigration. In other words, how can one move from politically motivated emigration to a political organization of emigration?

It should be noted that the history of Russian political emigration has rather deep roots in the past of the country, starting from the time of Muscovy. Perhaps the very first famous political emigrant from Russia was Prince Andrei Kurbsky, who left for the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. While in Livonian Wolmar and the lands of the Commonwealth, he exchanged lengthy letters with Ivan the Terrible, reminiscent of the beginning of treatises from the field of the political or moral philosophy of that time, rather than examples of the epistolary genre. However, the opponents grasped the very essence and meaning of the contradictions existing between their positions literally in two short and simple phrases. “In Rus’, the ruler is like Satan, who imagines himself to be God,” Kurbsky denounced the Moscow tyrant tsar. “We were always free to favor our lackeys, as we were free to execute them,” the autocrat retorted in response to him4. However, the experience of a sixteenth-century political émigré hardly seems relevant to the position of a twenty-first-century political émigré.

Emigration from the Russian Empire before the First World War is well-known and quite studied, which has a political background as well. The next large-scale and tragic in its scale, as well as the more studied one, is the emigration following the October Revolution and the Civil War. Understanding emigration in the modern sense of the term, sociologists, as a rule, distinguish six chronological “waves of emigration”5 in it. Namely: First Wave (1891–1914), Second Wave (1918–1922), Third Wave (1941–1945), Fourth Wave (the 1970s–1980s), Fifth Wave (1989–1999), and Sixth Wave ( 2000s – to our time). In this case, emigration from Russia stands apart after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine6 (especially after the announcement of the so-called “partial mobilization”; in the latter case, the problem, moreover, is often the apoliticality of those leaving the mobilization, the vagueness of their position in the question of the initial attitude towards the Russian invasion), which is currently unfolding right before our eyes. However, for the last mass departure of Russians outside the country to be periodized and assessed as a separate stage of emigration, probably too little time has passed. Our attention will be drawn to the emigrants of the Sixth Wave, and the problems of their political organization. Creation of a common network of interaction between the diaspora, and, possibly, political institutions of representation, if the demand for such will be recognized by consensus by the majority of active participants in the communities of intra-emigrant dialogue.

Within the framework of the so-called Putin’s Exodus of 2000–2018 (the expression of the sociologists Herbst and Erofeev from their report of the same name), Russia missed from 1.6 to 2 million citizens7. Moreover, the rate of departure from the country increased: 122.7 thousand people in 2012, 310.4 thousand in 2014, 440.8 thousand in 2018 (only according to official data). Emigrations of 2000-2010 had their characteristics and their reasons, sometimes far from direct correlation with the political situation in the country. Many of those who left the country during these years took this step for economic, and not for political reasons. Once in the countries of Europe and the USA, or choosing another direction of their emigration, these people decided, first of all, they were immersed in solving the problems of their material well-being (of course, except for individual cases of political refugees8). For many of them, the situation of February 24, 2022, became a kind of “shock politicization” point, when, perhaps for the first time in their lives, they faced the situation of having to make an unambiguous choice of political and moral stance against the backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. One of the forms of efforts for new politicized emigrants who feel responsible for the aggressive policy of their country was the cells of the Anti-War Committees that arose in the capitals of many European countries: their members provide volunteer assistance and assistance to Ukrainian refugees in the EU countries, thus supporting Ukraine in its struggle for freedom and independence, confirming and proving the practically well-known thesis that humanitarian tasks are now becoming political tasks9.

For the emigration of 2011–2014, on the contrary, the main reasons, according to experts, were already political events (at first, the “Bolotnaya case”, and a few years later, the annexation of Crimea)10. The annexation of Crimea and the war in the southeast of Ukraine became the impetus for the emigration of a huge number of Russian citizens. This opinion is supported by a number of statistical data. Since 2012, the base of repressive legislation has been constantly growing as part of the “conservative turn” project, the protection of “traditional values”11 and the “crackdown”. The laws on “foreign agents”, and “undesirable organizations”, to which the law on “enlightenment activities” has been added since the spring of 2021, already call into question the possibility of carrying out a whole list of specific types of activities. Politicization intensified against the backdrop of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the assassination of Putin’s well-known opponent Boris Nemtsov, and even earlier, the re-election of Putin himself to the presidency in March 2012, and other high-profile and resonant events that took place in the internal and external political life of Russia12.

Returning to the past and current political emigration in general, as well as its perception by Russian opposition politicians, it is important to note the existence of two political strategies: the separation of “Russian” and “emigrant” politics, while the second is supposed to be seen as clearly secondary and does not deserve special attention for the application of resources and opposition efforts. The first strategy is followed by associates of the oppositionist Alexei Navalny’s team, whose paradoxical position, however, is that they are currently mostly emigrants13.

The dispute between the “Russian” oppositionists and the “emigrants” develops into a larger dispute between those who left and those who stay, which, like any textbook Russian dispute, threatens to turn into “eternal”. According to the author of this article, such a dispute is currently devoid of any actual meaning, just like the dispute about the “lifetime” allotted to the Putin regime by the inexorable course of history, it is not so important what will serve as fuel for its acceleration: activity of political emigrants, external political forces or internal processes in Russia itself, which can lead to a situation of serious turbulence and destabilization of the regime. In the following paragraphs, we will briefly outline some common positions.

Among those who believe that in the current historical perspective, the option in which the Putin regime, having suffered an inevitable defeat in Ukraine, nevertheless retains (or even strengthens) its position within the country, quite popular examples confirming this point of view is comparing the state of affairs in Russia with North Korea, Cuba or Iran. Sometimes there is a parallel with Iraq during the Saddam Hussein regime, which, after a crushing defeat from the United States and allies in the Gulf War from August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991, for the restoration of Kuwait’s sovereignty, managed to hold on to power for another whole 12 years, until he faced direct humanitarian intervention by the United States on his territory. It will not be difficult to guess that Hussein’s Iraq is taking the place of Putin’s Russia in the above example, and Kuwait is taking the place of Ukraine. The trajectory of the path and further prospects of the Russian emigration itself in such optics are seen by analogy with the Cuban one14.

In contrast to them, in turn, there are arguments about the fundamental incompatibility of countries that throughout their entire modern history existed under authoritarian (or completely totalitarian, as in the case of the DPRK) regimes, and Russia, a country that, on the contrary, began its path in modernity as a country with a democratic (albeit relatively) and pluralistic competitive political regime that arose on the ruins of the past totalitarian ideological imperial project. In addition, attention is paid to regional (in the case of Iraq), religious (Iran), and other specifics, which quite significantly distinguish the cases of these countries from the Russian one.

Nevertheless, it is extremely important to remain sober and be aware that all these predictive models are like thought experiments and do not claim to be the ultimate truth in describing the current, and even more so, the distant political future of our country. It is not possible for us to predict with an absolute guarantee how the collapse of the Putin regime will nevertheless occur, what event will be the “last straw” here, will play the role of a trigger for change or a “black swan” that marks the end of the current Russian government. However, I repeat, a positive or negative answer to the question of how long to wait for the dismantling of the regime does not matter much. Since, regardless of the answer, in the event that the state of affairs in emigration and the topic of its political consolidation is not an empty phrase for us, the following steps must be taken:

-

- 1. To create public structures that provide comprehensive assistance (legal, financial, informational, etc.) to people who are forced to leave Russia for political reasons;

-

- 2. To create cultural and educational programs and platforms for interaction and development of political emigrants from Russia, which would allow to continue work on the formation of high-quality knowledge and ideas about modern Russian society, as well as democratic values and ideas15;

-

- 3. To create political representation bodies for emigration, in order to achieve institutional recognition as a legitimate participant in the political dialogue on the part of governmental and other official structures of the EU and the USA.

The productive implementation of the above three points, in turn, involves seeing the phenomenon of Russian emigration in two mutually complementary optics. First, emigrants as a humanitarian resource. Preservation of human capital, which is also important for the future of Russia after Putin, and in the present — capable of providing assistance to Ukrainian refugees and compatriots who remained in a country that has slid into a dictatorship. Secondly, emigration as a political force. And here, one of the ways to effectively use this resource, we see the further development of the conference of the Free Russia Forum as the most authoritative platform for the interaction of the opposition abroad, positioning it as a tool for organizing and institutionalizing Russian political emigration as the first steps along this path have already been taken16. With a high probability, the FRF (as, indeed, any other opposition movements, it doesn’t matter if they are of a coalition type, or closed on the figure of a specific opposition leader) will not be able to become the main actor of the coming changes in the country. Since the circumstances were such that after the start of large-scale aggression against Ukraine, other forces entered the scene, making Russia more dependent on external factors than on internal dynamics (this is the obvious paradox of Putin and his government, who proclaimed among the main achievements of his super-long presidency “protection of sovereignty” and “independence” from the so-called “collective West”, which in fact doomed Russia to complete dependence on external conditions: the speed of the counteroffensive and successes of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as well as the reactions to Russian aggression from the democratic world).

Nevertheless, the Forum, as a free platform for the interaction of anti-Putin forces, is absolutely capable of preparing the Russian opposition and the émigré community for the situation that will come after the fall of the regime. The organizers of the FRF themselves speak about this, following the results of the Third Anti-War Conference17. On the other hand, other platforms are also important, within the framework of which the process of consolidating grassroots emigrant movements is carried out. At the Gathering of Civic Anti-War and Humanitarian Initiatives held in Berlin on December 3-4, was announced the launch of the Free Russians project, which has a global and ambitious goal of uniting the scattered emigrant grassroots communities in Europe into a horizontal structure of solidarity18. But even regardless of the success or failure of a particular project, in general, the significance of such conferences is quite difficult to overestimate, since it is at them that a lively and free discussion and exchange of experience takes place, during which the Russian emigration acquires its own unique face, different from the image of Russians burdened with resentment and militarism imposed on Putin’s Russia. The practical experience that the participants of volunteer groups share with each other at these platforms organically complements the theoretical vision of a comprehensive strategy for anti-war, humanitarian and political activities offered by experts and politicians invited by the organizers as speakers and moderators of discussion panels, workshops and sections.

It should be recognized that Russian emigration (both those who initially left for political reasons and politicized by the shock of the war unleashed by Putin’s Russia) today, for all the complexity and heterogeneity of this phenomenon, is one of the most important resources for determining and achieving the political tomorrow of the future post-Putin Russia. The task of modern Russian politicians is to use this valuable resource wisely, for the benefit of both the emigration itself and the future of Russia. ______________________________

1. According to current UN estimates, about 11 million people from Russia live abroad; this is the third highest figure in the world after India and Mexico. // World Migration Report: https://www.iom.int.

2. Link to Ilves’ original post in English: https://twitter.com/IlvesToomas/status/1595061770523398144. Translation and discussion around it: https://www.reddit.com/r/tjournal_refugees/comments.

3. More than half a million people left the country after the Spanish Civil War. Throughout the Francoist period, Spain was a country of both political and economic emigration. The latter, towards the end of the Franco regime, became so massive that by the mid-1970s approximately 3.3 million Spaniards left the country in search of work (10% of its then population). Source: Ponedelko G. Migration in Spain // World Economy and International Relations No. 9, 2015. P. 80-91.

4. Correspondence between Ivan the Terrible and Andrei Kurbsky. M .: “Literary monuments”, 1979. pp. 136, 158.

5. Herbst, Erofeev. Putin’s Exodus: The New Brain Drain.

6. According to the official estimate of Rosstat, 419 thousand people have left the country since the beginning of 2022. For a more detailed assessment of the role and importance of those who left after 02/24/22 in the overall picture of Russian emigration and their impact on the demographic situation, see, for example: “How many people left Russia because of the war? Will they never return? Can this be considered another wave of emigration? Demographers Mikhail Denisenko and Yulia Florinskaya explain. Meduza website material: https://meduza.io/feature/2022/05/07/skolko-lyudey-uehalo-iz-rossii-iz-za-voyny-oni-uzhe-nikogda-ne-vernutsya-mozhno-li-eto-schitat-ocherednoy-volnoy-emigratsii.

7. Data from the Atlantic Council report. Putin’s Exodus: The New Brain Drain. Authors: John Herbst, Sergey Erofeev, 2019 Access via link: https://publications.atlanticcouncil.org/putinskiy-iskhod.

8. Traditionally, the political emigration of the 2000s had two centers of attraction — London and Kyiv. The first became such mainly due to the emigration of Boris Berezovsky and Yukos managers (and later, Mikhail Khodorkovsky himself). The second, due to its proximity, accessibility (lack of visas) and the relative cheapness of life, as well as relatively greater political freedom (especially after the Orange Revolution of November 2004 — January 2005). Paradoxical as it may seem, given the specific position of their political organization, at first, the National Bolsheviks, who were subjected to serious political repressions, most often moved to Ukraine. In particular, in 2008, Ukraine granted political refugee status to Olga Kudrina, a participant in high-profile National Bolshevik “direct actions”, who soon after that created her own organization, the Union of Political Emigrants.

9. The pages and groups of the Anti-War Committees are represented in popular social networks. For example, here is a link to an open group of the Prague Russian Anti-War Committee on the Facebook social network: https://www.facebook.com/groups/951685019071511.

10. In the period 2011-2014 great importance acquired the departure abroad of iconic political, social and cultural public media personalities (politician Garry Kasparov, eco-activist Evgenia Chirikova, writer Boris Akunin, etc.).

11. About the “conservative turn” as a phenomenon of new populist politics in modern Russia, and in the political discourse of Western countries, in particular, the Russian leftist theorist Ilya Budraitskis wrote: Ilya Budraitskis. Paradoxes of the conservative turn in Russia / Budraitskis I. The world that Huntington invented and in which we all live. M.: Publishing house Tsiolkovsky, 2020. // On the conservative turn as a global trend: see Budraitskis I. The reactionary spirit of the times. Conservatism Talk / Colta Article: https://www.colta.ru/articles/raznoglasiya/14228-reaktsionnyy-duh-vremeni-razgovor-o-konservatizme.

12. The social and professional composition of the Russians who emigrated is also interesting, so, according to the Herbst-Erofeev report, the following professions were employed by emigrants from Russia before they moved: the majority were students (17%), primary / middle managers (16%), employed in information technology and programming (10%), arts and culture (6%), science and research (5%), finance and economic analytics (5%), jurisprudence and law (5%), journalism (4%). These people are involved in the social life of their host countries, actively use social networks and read the media (52% “closely follow the political life of the new country”). Those who left after 2012 are more interested in Russian politics (which again confirms that they are more politicized than those who left before 2012. In their opinion, only the end of the Putin regime can help their country begin to develop “normally”. Based on the idea of “no return” , emigrants hardly understand their own role: on the one hand, they are afraid to dissolve in Western Europe, speaking of themselves as a kind of “Russia in reserve”, demonstrating their readiness to participate in the construction of a “beautiful Russia of the future” in the future; on the other hand, it is obvious lack of social resources to create strong diaspora institutions (Report of the Atlantic Council: “Putin’s Exodus”. Authors: Herbst D., Erofeev S., 2019. Access at the link: https://publications.atlanticcouncil.org/putinskiy-iskhod).

13. So the actual head of Alexei Navalny’s organization, Leonid Volkov, regularly emphasizes that they are “engaged in Russian politics, and not solving the problems of emigrants.” From a similar position, the ex-head of Open Russia, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, began his foreign political work, whose main project (in fact, Open Russia in its various incarnations: Open Russia / OR / Otkrytka) proclaimed as one of its main goals is to help opposition (or even relatively “systemically” opposition, given the realities of the Russian political regime) candidates in election campaigns at the municipal and regional levels. Later, however, he significantly corrected his initial position, announcing the launch of such projects as the Anti-War Committee and the Ark (https://kovcheg.live), whose activities are aimed at helping Russian citizens who have decided to leave the country due to both his anti-war position and general disagreement with the political course pursued by the current regime in Russia.

14. See, for example: Denis Bilunov. Not home and not death. How Russian emigration can repeat the fate of the Cuban. Article on The Insider website: https://theins.ru/obshestvo/255901.

15. As an example of a successful cultural and educational platform for Russian emigration in the Czech Republic, we can cite the Kulturus Contemporary Culture Festival, founded by artist Anton Litvin. The festival has been held annually since 2012, acting as an important cultural gathering point for the Russian emigration, at the same time, it managed to acquire the status of a significant event in the Czech cultural life, contributing at the same time to the process of integration and preserving the identity of the Russian diaspora. Kulturus website: https://www.kulturus.cz. // An example of a much more serious educational and research platform, for its part consolidating the Russian diaspora of the Czech Republic by intellectual means (namely, organizing public lectures by famous Russian-speaking speakers, presentations of books on topical topics), is the Boris Nemtsov Academic Center for the Study of Russia at the Karlov Faculty of Philosophy University in Prague. Website of the Boris Nemtsov Center for Russian Studies: https://cbn.ff.cuni.cz.

16. The creation of the Russian Action Committee as a coalition association can be considered such a step. Among the tasks set by the RAC, an important place is occupied by lobbying the interests of the Russian emigration, in order to solve the problems associated with indiscriminate restrictions and prohibitions extended to all carriers of the Russian passport, which arose as a result of the sanctions policy of the European Union against Russia in response to military aggression against Ukraine.

17. Garry Kasparov: “The future of the 21st century depends on where Russia goes.” // Interview on the Belsat website: https://belsat.eu/ru/news/04-12-2022-kasparov-ot-togo-kuda-pojdet-rossiya-zavisit-budushhee-xxi-veka.

18. Website of the Congress of Anti-War Initiatives in Berlin on December 3-4: https://antiwar.in // Article on Radio Svoboda: https://www.svoboda.org/a/v-berline-proshyol-antivoennyy-kongress-grazhdanskih-initsiativ/32162173 // DW report on the Congress in Berlin: https://www.dw.com/ru/antivoennyj-kongress-v-berline-mogut-li-sami-rossiane-ostanovit-putina.